Wind Warrior 2000

by Kent Multer

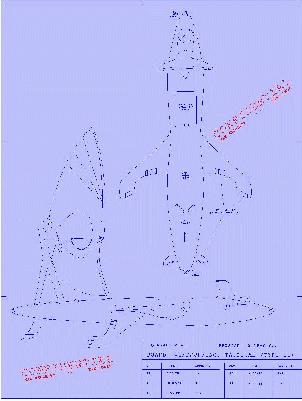

Click on the image to see a larger version (about 45k bytes).

Wind Warrior 2000by Kent Multer |

Click on the image to see a larger version (about 45k bytes). |

It was, as they say, a dark and stormy night. In fact, it was probably the darkest and stormiest I'd ever encountered. Must be blowing 50 or 60 knots out there, I thought, as I watched the rain slosh against the portholes, and I felt, rather than heard, the walls shuddering in the heavier gusts.

There was an odd feeling in my gut, sort of tight but loose at the same time; familiar, but I couldn't quite place it. I stretched again, trying to loosen the kinks in my muscles from a twelve-hour plane flight. Suddenly I wished I was back on Maui, riding a wave, or just kicked back on the lanai with a cold drink, watching the sunset.

But that was definitely not the case. I swung my head through one more neck roll, and returned my attention to the man with the crew cut and the rumpled suit.

"The kidnappers have stashed the ambassador on an offshore oil-drilling rig, much like this one, but further out in the Gulf," he was saying. "They've got it protected with every kind of radar and sonar they can get, plus active defenses in the form of anti-air and anti-ship missiles, heavy guns, and torpedoes. They think it's safe against any kind of rescue attempt ... and they're almost right.

"But our analysis team figured out an angle that they haven't thought of. A windsurfer is small and fast, and it can be built with almost no metal, so it won't show up on their radar. Since it has no engine, their sonar isn't likely to detect it. Plus, it can get in and out during weather conditions that no other craft could handle.

"During a storm, they won't be expecting an assault, so they'll be off guard. And with hurricane season just beginning," he added, jerking a thumb toward the tormented porthole, "we should have plenty of good opportunities for a rescue in the next few weeks."

He looked at me as if I was supposed to say something. The wind roared again. The walls shook. So did I. Suddenly I recognized that yucky feeling in my guts: fear of high wind!

I hadn't felt that feeling in a long time. Windsurfers go through a familiar cycle as they learn to sail in stronger wind. You start out on mellow days when it's blowing 5 to 10 knots, and after a few weekends, you think you're getting pretty good. Then one day, you're feeling cocky, and you go out in 10 to 20, and it's like being a beginner all over again: falling a lot, turning too far upwind and losing your power, all the same mistakes. But after a few hours, you get the hang of it, learn to react a little faster, and you're happy again ... until you try 20 to 30 knots. And so on, and so on.

I'd been on Maui long enough to get pretty comfortable in 30 to 40 knots. But this ... "You want me to sail my board out, pick up some guy, and bring him back -- in a hurricane?"

"Not your board, good God, no." He smiled. "We've got something special for you to ride. I think you'll like it."

He led me through a door, down a hall, and into a long, unfinished room: the oil-platform equivalent of a garage. At one end was a steel door that rattled and flexed under the impact of the storm. Nearby was a small crane, rigged so that it could be swung out through the open door. At the other end of the room was a huge pile of chains, lengths of pipe, and wrenches the size of your arm. Obviously it had all been piled there to clear some space for the two boat-like objects perched on sawhorses in the middle of the room.

Click on the image

to see a larger version (about 100k bytes).

Click on the image

to see a larger version (about 100k bytes).

"Tom! Here's your teammate," called my escort. A man in a drysuit had been leaning over one of the objects. Now he turned with a catlike grace that hinted at years of kung fu practice. When I saw the Japanese cast of his face, though, and the short bow with which he greeted us, I changed my appraisal: probably ninja training.

He smiled and extended his hand to me. "Toru Yamamatsu, but call me Tom. I've read your file; glad to have you along." I shook his hand, but something was bothering me as I looked past him at the two vehicles on the sawhorses. "Hold it! You expect us to ride those in a hurricane? They must be fifteen or sixteen feet long!"

"Yours is closer to twenty," he replied, smiling again, "but don't worry, it'll carry you just fine." The rule for sailboards is, the higher the wind, the smaller the board. Beginners start out on twelve-footers that are nice and stable. But in high wind, they're clumsy and hard to control. My current favorite for Maui conditions was an 8 1/2 footer. If I was crazy enough to sail in a hurricane (and some folks do), I'd probably go down to a 6 or 7. "I promise you," continued Tom, "it's different from anything you've ever seen."

"It is kind of pretty -- for a longboard," I admitted, as I walked up for a closer look.

"It has to be long, in order to carry your passenger. There's a compartment for him in the middle, near the center of gravity, so the board will handle the same after the pick-up."

He pointed toward the footstraps. "There are sensors in the deck here. They pick up changes in your foot pressure and stance. The on-board computers read that, and translate it into commands for the flaps on the fins. Once we get the system tuned to your body and sailing style, it'll turn and jump as quickly and lightly as any shortboard."

Instead of a simple tail fin, the board had an assembly like the tail of a jet. There was a large vertical fin, with a horizontal wing across the bottom forming an inverted T shape. The trailing edges had small movable flaps on them. Further forward, near the mast foot, two small wings extended out and downward from the rails; they also had flaps.

It was beautiful. It had that kind of understated, graceful beauty that you find in aircraft, musical instruments, and some weapons: things whose shape is governed not merely by some designer's sense of style, but by the laws of physics as they apply to something that must do a difficult job with efficiency and precision.

A short wing was mounted above the nose, like the spoiler on a racing car. I pointed at it. "For jumps?" "Partly," Tom responded. "In max conditions, the combined wind and board speed can add up to almost 100 knots. At that kind of speed, you need aerodynamic control all the time. Of course, when you do jump it, it's like ... well, you'll see." His smile was restrained, but I saw the light in his eyes that had to mean boardhead nirvana. 100 knots! The thought of it turned my stomach to mush. Even so, I was beginning to like the sound of this little excursion.

Tom gave the hull a friendly slap. "This girl is smart; she's got more computers in her than some aircraft. In addition to the board and sail control, you've got radar for weather and navigation, forward and rear video with boosters for night vision, infrared for looking through bad weather, and two-way voice and data links to me and the command post. All the visuals come out to a heads-up display that's projected on your helmet visor. Most of it's automatic; the rest can be controlled either by voice, or by the controls here." He pointed to the control panel on the chest of his dry suit.

I had been wondering about that. At first I had thought he was wearing a standard all-weather suit, with the little backpack hump for the heating and air conditioning unit. Now I realized that his suit was a little different. For one thing, there were quite a few extra buttons on that control panel.

The next morning, I was wearing an identical suit, sitting on my board as it was lowered into the water. When it touched down, I released the winch cable, and immediately began drifting downwind; it was still blowing 50 or so. A wave crashed over my head, and suddenly the suit woke up. A row of numbers and other symbols appeared along the bottom of my visor.

"Immersion," said a female voice in my earphones. "All systems fully functional."

"Who's there?"

"That's the board," came Tom's voice in my headphones. He had been lowered down ahead of me, and was a few hundred feet further downwind. "It's ready to go, so let's rig up."

The sail was folded into a long bundle along the deck. The rigging lever was painted with high-visibility yellow, and lettered with the word "PULL" in English and Japanese. "Ganbaro!" I said, and pulled it. The sail hinged away from the deck, and leaned over to the downwind side of the board. I grabbed the uphaul rope, and worked my way up to grab the boom as it popped into position. By the time the sail finished opening, I had it in waterstart position, so I put my feet on the deck, sheeted in, and let the sail pull me up out of the water. Pretty good for a first try, I thought. Then I tilted my head back to examine the sail, and what I saw startled me so much I nearly got slam-dunked.

Ever watch a hawk riding an updraft? You know how he has those feathers like fingers out at the end of his wings? That's what this sail had. Fingers up there, twisting and shifting in the wind like part of a living, flying creature. I could hear the gusts buffeting around my helmet, I could feel them rippling over my suit; but the boom stayed firm and steady in my hands.

I hooked the boom to my harness and stepped into the footstraps. "Tactical display," I said to the board; it was one of the commands I had been briefed on the night before. A grid of colored lines appeared in front of my eyes. The display showed that Tom was somewhat upwind of me, heading away on a straight reach. I steered a course to intercept him. As I leaned back, the board speed display showed 30 knots. 35, 40 ... the board rose up until the hull was clear of the water, riding on the wings like hydrofoils.

As I'd been promised, it was a joy to sail. The computer compensated instantly for gusts and chop. The board felt like it was on rails, yet it responded smoothly to every twitch of my toe. The swells were running about 20 feet. I kept the board on the surface; not ready to try any jumps yet, thank you! The radar showed that I was closing on Tom. Then I saw him up ahead, just as an especially large wave hove into view.

It looked like maybe 40 feet, or maybe 50; I don't know, I'm not used to those kind of numbers. The top of the face was nearly vertical, swirled with foam like icing on a cake. Tom didn't even change course. He shot like a rocket up the face, dove into the mass of foam, and disappeared. "What the fuck," I thought, "let's go for it." The speed display showed 52 knots. My stomach felt like dry ice.

As I curved up the face, the G force squeezed me down till my butt nearly touched the water. I pushed hard with my legs and straightened up a bit. Then I hit the lip, and for a moment there was nothing but the white foam and a crashing noise in my ears. I relaxed the way I always do when I realize I've blown a jump, getting ready for the fall. I think I blacked out for a moment.

The next thing I remember, I was hanging in the air; there was no water anywhere to be seen. Well, no: obviously the Gulf was still there, but it was -- 75 feet away? 100 feet? I don't know. It could have been half a mile. There was no ocean sound, just the wind singing in the rig and rushing past my helmet. I watched drops of water spilling off the board and disappearing under my feet.

The mast, I realized, had folded over at some kind of elbow joint just above the boom. Most of the sail was horizontal, over my head like the wing of a hang glider. Off to my right, the "fingers" of the sail seemed to be wiggling around like someone doing sign language at 30 words a minute. But I didn't want to turn my head to look directly at it. I felt like, if I did, I'd disturb my balance and go out of control. Actually, I think I was too petrified to do anything but hang on and look straight ahead. I could see the forward wing tilting and turning to keep the board level.

Suddenly I saw Tom out ahead of me; his sail was folded over like mine. Then he splashed down, and the sail straightened back to its normal position. Nice landing, said the part of my brain that was still working. Then it was my turn, as the water was getting close. Closer ... I leaned back, shifting weight to my back foot, and the forward wing tilted up, lifting the nose of the board ... easy, not too far ...

KSSHHHH!!! Bend the knees, absorb the impact ... a blast of water across my visor, swept clean at once by the wind ... Hey! I made it! I'm still sailing, still in one piece. I heard a wild victory shout in my headphones. Then I realized it was my voice.

Then I heard Tom. "Not bad, not bad at all for your first try. Let's head back the other way; in this storm, we don't want to get to far from the platform."

"What's the problem? This ship can take it."

"Easy, kid. Don't get cocky."

Two hours later, I hung the drysuit back on its rack in the "garage." As I turned to leave, I gave the board an affectionate pat. Actually, if I'd been alone, I probably would have given it a big hug and a kiss on the nose. My guts felt warm and relaxed; I was ready for a shower and a meal.

As Tom and I walked away, I turned back for one last look. Then I noticed something. "How come your board's so much smaller than mine? And what are all those extra fins for?"

"Different mission profile," he replied. "Your board is the personnel carrier; mine is the gunship."

"Gunship? ... ?"

"This is no Sunday at the beach, man. The kidnappers are tough and well armed. The plan calls for us to get in and out with minimal, uh, 'engagement;' but these things never go quite the way they're planned. Of course, your board has some weapons, too. We'll practice with them tomorrow."

Suddenly my guts were full of ice again.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Blake Richards of Northwave Sails for the idea of a sail with fingers.

All text, images, designs, and other features created by Kent Multer

This page and all its contents are copyright © 1996 by Kent Multer.